As the climate has changed in Alaska over the past several decades, invasive plants and area burned by wildfires have both increased. Invasive plants are non-native species that have been introduced from a different region. Yet not all non-native species are invasive. Invasive species are often defined by three features:

-

Originate from another region (non-native).

-

Spread rapidly or aggressively, often outcompeting native plants.

-

Have harmful effects on the environment, economy, or human health in their new habitat.

In Alaska’s boreal forests, the cold climate and small human population historically limited the introduction and spread of non-native species. Invasive species in Alaska tended to stay in areas dominated by people.

Recently, however, more non-native species are growing in Alaska’s boreal region. Warmer temperatures, increased human disturbance and transport, and more area burned by wildfires may all work to weaken the resistance of the boreal forest to non-native plants. Increases in invasive species in Alaska’s boreal forests in recent decades support this idea. Between 1941 and 1968, Alaska saw approximately one new species introduction per year. More recently the number of non-native plant species has surged, growing to about three new plant species per year between 1968 and 2006.

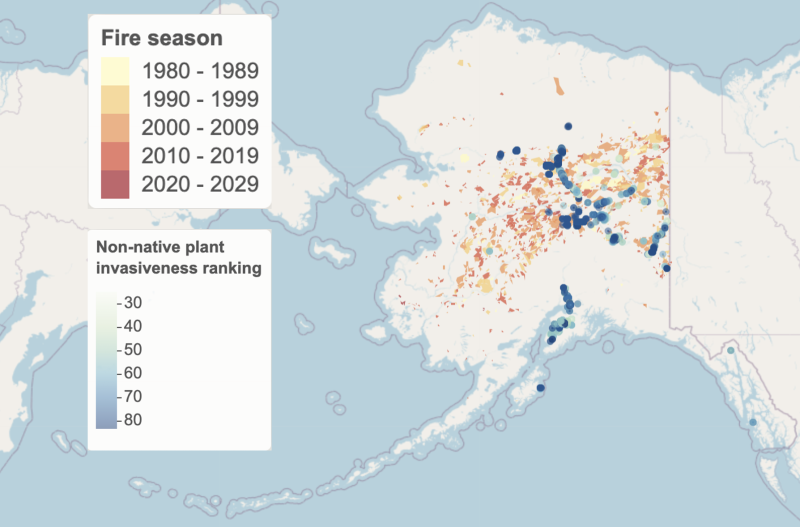

Image

Adding to the non-native species problem, fire patterns in Alaskan boreal forests have shifted in recent years, increasing the opportunities for non-native plant establishment. In the 2010s, the number of late-season fires increased. The amount of burned area nearly quadrupled compared to the previous decade. Since 1980, over 1500 fires have burned in the same spot only 20 years after the previous fire. Also, between 2000 to 2020, fires have been reoccurring in the same spot sooner. Non-native plants have been observed spreading from busy roadside corridors into burned areas in Alaska’s boreal forests. In general, burned areas are more vulnerable to non-native plant introduction than unburned areas in Alaska because existing vegetation is removed in wildfires. After the very large fire years of 2004 and 2005, land managers in Alaska were worried that the large areas disturbed by wildfire along major roadways could be at risk of widespread invasion by non-native plants. However, new research suggests that the long-term persistence of non-native plants in these areas is unlikely. University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) surveyed 300 transects within recent burn perimeters along three highways in interior Alaska. In their initial survey in 2007, 27 transects had invasive plants spreading from roadsides into burned areas. In 2023, UAF researchers, supported by the Northwest Climate Hub, revisited transects and found only six locations where invasive plants remained. Those six locations had several disturbances between 2007 and 2023 (primarily road repair and maintenance). This means that the likelihood of re-introduction in these six transects was higher.

Which non-native plants are being found?

Image

Certain species have a much higher relative frequency within burn perimeters than in unburned areas, such as white sweetclover (Melilotus albus). Scientists and community members have observed 77 different non-native plant species growing inside burn perimeters. Of those 77 species, about half have been spotted in burn perimeters more than 10 times. These species have been found growing in recently burned soils:

-

White sweetclover (Melilotus albus)

-

Common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

-

Narrowleaf hawksbeard (Crepis tectorum)

-

Bird vetch (Vicia cracca)

-

Smooth brome (Bromus inermis ssp. inermis)

Many of these plants (white sweetclover, smooth brome, and narrowleaf hawksbeard) are widespread throughout the state. In native boreal forests, some of these species have been shown to impact the native ecosystem. For example, white sweetclover has been found to alter pollinator behavior and shade native seedlings.

What factors influence the vulnerability of burned areas to plant invasions in boreal forests?

One major factor that determines the likelihood of invasive plants establishing on burned land is propagule pressure, or the number of individuals and seeds and the frequency of their introduction. Propagule pressure in Alaskan boreal forests is typically determined by the abundance of non-native plants on roadsides. The more non-native plants on roadsides, the more likely they are to invade a burned area. Therefore, burned areas near heavily infested highways are more vulnerable to invasive plants. Another major factor influencing a site’s vulnerability to invasion is regional differences in soil composition and pH.

Image

Post-fire dynamics and time since the last burn also affect vulnerability of non-native plants establishing. Older burns provide more time for native vegetation to reestablish and tree canopy to regrow. Sites where mosses and liverworts regrow quickly after a burn can provide a buffer for non-native plant growth. Also, many invasive plants in Alaska are not shade tolerant. Therefore, sites where it takes longer for the canopy to close or that develop into open canopy forests allow invasive plants more time to establish a seed bank. Other potential factors may affect the vulnerability or resilience of a burned area to invasive plants. Many of these are much-needed areas of research in Alaska. These include information about the presence and development of invasive plant seedbanks in the soil, soil microbial communities, and species interactions, which can facilitate or slow invasive plant populations.

Wildfire severity has not been shown to change the vulnerability of a site across all non-native species. However, it does play a crucial role in which specific non-native species can germinate and grow successfully. High-severity fires remove thick organic mats, allowing species like white sweetclover and dandelion to establish. Low-severity wildfires promote the growth of bird vetch, narrowleaf hawksbeard, and smooth brome grass.

Multiple disturbances, such as overlapping road construction and previous burns, increase vulnerability to invasive species. Understanding these factors helps manage and mitigate the detrimental effects of non-native plant invasions. This will protect vulnerable burned areas of Alaska's boreal forest and maintain native forest ecosystems.

How can Alaskans reduce the spread of non-native plants into boreal forests?

Although research suggests that non-native species infestations decrease over time, reintroduction can occur in places with multiple disturbances. Also, sites where burn scars and human disturbance intersect have a high potential to allow non-native plants to spread into wilderness areas. Therefore, these areas have been priority locations for post-fire non-native plant surveys and monitoring. To reduce the spread, invasive plant specialists can continue monitoring these sites.

Citizens can also prevent invasive species spread with proactive measures. By being familiar with common invasive plants, Alaskans can identify and treat invasives they see on their own properties. Seeds can travel on all gear, from road and trail maintenance equipment to recreational equipment like boots, vehicles, bikes, and all-terrain vehicles. Properly cleaning all gear and vehicles before using them in a new location can prevent seeds from spreading. Most importantly, any non-native plants should be reported to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Invasive Species Reporter. Through proactive prevention, monitoring, and management strategies, the combined challenges of climate change, increased wildfires, and invasive species can be addressed, supporting the resilience and sustainability of these vital ecosystems for future generations.

This article provides a summary of a more in-depth technical report and webinar by researchers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Bonanza Creek Long Term Ecological Research Program.