Reading time: 10 minutes

Here at the Northwest Climate Hub, we recognize that extreme weather events and effects of climate change may have caused damage or distress to many of our readers. Reading about extreme weather events may be triggering so if you are suffering from mental health impacts because of climate change, please reach out to the Disaster Distress Helpline.

What factors are contributing to coastal storms in western Alaska?

Along the Bering and Chukchi Seas, the west coast of Alaska is regularly affected by intense storms. In the past, a protective barrier of sea ice typically formed along the Chukchi coast and Kotzebue sound by early October, and the northern Bering Sea by late October or early November, before winter storms could impact the coastline. As Alaska’s climate rapidly changes, sea ice is forming later in the year and sea levels are rising in much of western Alaska, increasing the impact of storms on coastal communities. As protective coastal sea ice declines, intense storms could increase coastal erosion, flooding, salinization of freshwater resources, and damage to infrastructure. These impacts could create food insecurity and require undesired relocation of rural villages.

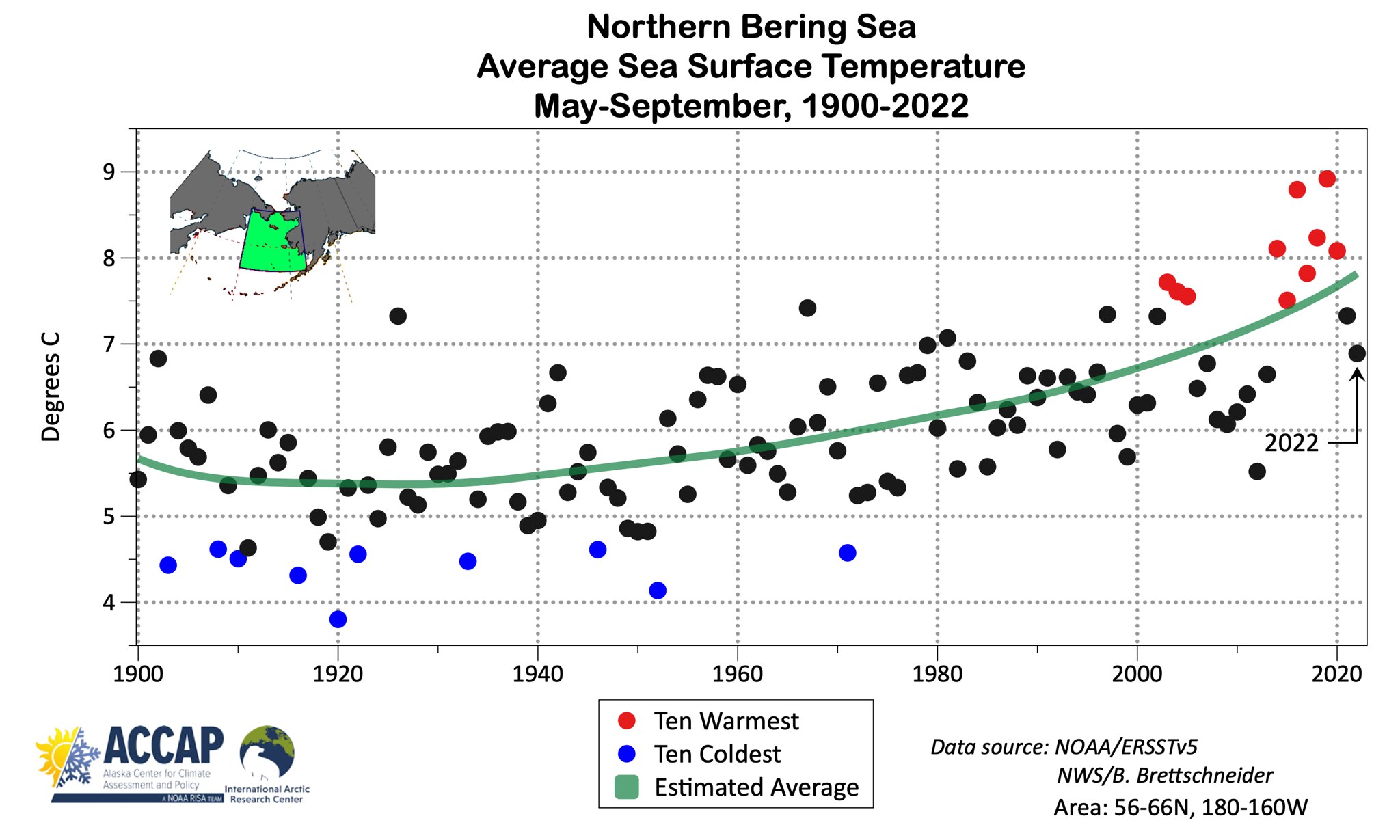

Rising Ocean Temperatures: Rising ocean temperatures in the Arctic are expected to increase storminess, though there is no evidence of increased storminess in the Chukchi or Bering Seas to date. However, rising ocean temperatures cause more evaporation to occur in the atmosphere, increasing air temperature and moisture, and acting as fuel for storms like September 2022’s ex-typhoon Merbok. As ocean temperatures rise, storms could form in areas where the water was previously too cold to support storm development.

Decreasing Sea Ice: Even marginal amounts of coastal sea ice can offer protection from storms by lowering wave energy. Sea ice is typically present along the west coast of Alaska from November to April, and sometimes longer. However, rising temperatures have decreased sea ice coverage and delayed sea ice formation. On the Bering Sea, sea ice coverage has declined by 26% per decade since 1980. On the Chukchi Sea, sea ice formation is occurring 35 days later than it did in the 1970s. Absent sea ice also contributes to increased storm surge (an abnormal rise of water generated by a storm, over and above the predicted astronomical tides) and coastal flooding and erosion, damaging infrastructure and forcing some coastal communities to relocate.

Ex-Typhoon Merbok

In September 2022, ex-typhoon Merbok made contact with western Alaska months before the formation of protective coastal sea ice could buffer communities from the impacts of powerful waves, flooding, and high winds. Storms of Merbok’s magnitude are more frequent in October or November, after protective sea ice has formed. Merbok was the strongest September storm to hit coastal Alaska in at least 70 years.

The storm formed west of Wake Island in an area of the subtropical Pacific where waters have historically been too cold for tropical cyclones to form. Traveling over the North Pacific Ocean, Merbok brought winds up to 75 mph, large waves, and widespread flooding to a thousand miles of Alaska’s coastline from Bristol Bay to the Bering Strait.

Residents of 40 communities in western Alaska impacted by ex-typhoon Merbok are predominantly Alaska Native and rely on harvesting and storing wild foods for their health. The intensity of the storm resulted in homes in remote villages, such as Newtok, to be ripped from their foundations by floods. In Shaktoolik, a protective berm was destroyed by large waves, leaving the community water supply vulnerable to saltwater inundation. In Nome, sea level was higher than it had been in nearly 50 years – 10.5 feet higher than the low-tide line. Airstrips, roads, and electric power infrastructure in many communities were damaged or inoperative. In many places, freezers failed, threatening food security. As sea ice coverage declines and temperatures and sea levels continue to rise, western Alaska could face storms of Merbok’s scale, timing, and impact more frequently.

What’s in a name: typhoon, hurricane, or cyclone?

In western Alaska, coastal winter storms can be caused by ex-tropical cyclones formed from poleward-moving tropical systems, or from strong temperature differences between air masses. Several notable ex-tropical cyclones have occurred in recent years, including ex-typhoon Merbok and ex-tropical Cyclone Nuri in November 2014.

A typhoon is a tropical cyclone in which the highest sustained surface wind is 74 mph. The term “hurricane” is used for tropical cyclones originating east of the international date line to the Greenwich meridian. The term “typhoon” refers to tropical cyclones originating west of the international dateline in the northern hemisphere (usually East Asia). If a tropical cyclone originates elsewhere, it is simply called a tropical cyclone.

Because some of the storms that impact coastal Alaska form east of Asia, they are referred to as typhoons. Most of these storms are also referred to as “ex-typhoons,” implying that the typhoon moved poleward and lost its “tropical” characteristics. An ex-typhoon’s primary energy source often starts as warm, moist tropical air. Then, the energy source changes to the temperature contrast between warm and cold air masses and sea temperatures found in the North Pacific Ocean. Cyclones can become ex-tropical and maintain winds of hurricane or tropical storm force.

Impacts of coastal storms on western Alaska communities

Coastal erosion

Intense storms in western Alaska have serious implications for coastal communities, with disproportionate effects on Alaska Native communities. Decreasing sea ice, thawing permafrost, and increasing storminess makes shorelines more vulnerable to coastal erosion. As sea ice melts earlier and forms later in the year, large waves and storm surge can batter coastlines, producing erosion rates up to 72.8 ft per year. In 2013, the village of Shishmaref saw 60 ft of shoreline erode in one storm. Coastal erosion threatens infrastructure, livelihoods, and wildlife habitat, and can also damage cultural sites that provide a record of human settlement in the area.

Flooding and storm surge

Flooding and storm surge are particularly concerning in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, a low-lying coastal floodplain in western Alaska. Because of the delta’s low elevation, communities are increasingly vulnerable to the effects of storm surge, up to 23 miles inland. Flooding and storm surge can increase infrastructure damage and threaten human lives. Freshwater and sanitation systems can be impacted by flooding, which can cause salinization of drinking water, damage to water and sewer systems, and disruptions to community septic and water distribution systems. Infrastructure damage can extend to roads and airstrips, limiting access and aid to impacted communities.

Changes to wild-harvested resources

Storms impact wild harvest activities, which provide a significant component of rural and Alaska Native diets. During ex-typhoon Merbok, flooding and storm surge reached such an extent that in places like Chevak, Alaska, ocean boats were scattered up to nine miles inland. Significant damage occurred to hunting and fishing camps, nets, and boat motors used for accessing camps. Some boats were only recovered in the winter when they could be retrieved with snow machines, though their expensive motors were destroyed by the storm.

Because harvest camps are commonly occupied in August, September, and October in coastal Alaska, storms occurring in autumn can prevent access to wild-harvested resources and impact crucial infrastructure, like boats, hunting camps, and freezers. These storms threaten wild-harvest practices, food security, and cultural practices of western Alaska and may result in changes to harvest and diet in many communities.

Loss of electrical power

Flooding and high winds can cause power outages, which can impact residents of rural communities in myriad ways. Remote communities can lose communication with the outside world, impairing contact with statewide aid resources. Because many of the impacted communities are so remote, repairs to infrastructure can be expensive and slow. In remote areas with limited access to store-bought goods, freezers are a necessity for community survival. Loss of electrical power and impacts from flood waters can cause freezer stores to spoil and lead to food insecurity.

In several coastal communities, wind energy generation has developed over the past few years, allowing communities to turn from diesel generators to a renewable form of energy for electrical power and heat. Ex-typhoon Merbok damaged some of this renewable energy infrastructure. For example, in Chevak, Alaska, 3 out of 4 wind turbines were damaged by the storm. Only one turbine remains functional to date. Repairs are likely to be slow and costly due to the remoteness of the community.

Community relocation

More than 87% of Alaska’s rural communities are affected by flooding and erosion. The Army Corps of Engineers found that 22 communities in western Alaska face imminent danger due to flooding and coastal erosion. Although some communities have implemented coastal protection resources, such as coastal berms and rock revetments, in several instances, rapid coastal erosion and flooding have damaged infrastructure and human health and wellbeing, and forced entire communities to consider relocation, including Kivalina, Shishmaref, and Newtok.

Alaska Native Villages faced with relocation must contend with daunting challenges. While seeking funding, managing risk, and planning community and construction activities, Alaska Natives must also maintain the local economy and attend to the mental and physical health of community members. Meanwhile, storms, floods, erosion, and permafrost subsidence continue to erode away land that Alaska Natives have relied upon for centuries. It is estimated that over the next 50 years, approximately $3.45 billion will be required to protect infrastructure in 144 Alaska Native villages determined to be at high risk of relocation. Meeting relocation needs will be a massive challenge for the state.

How can Alaskans prepare for intense storms in the future?

Vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans

Rural communities have displayed remarkable capacity for response and adaptation in the midst of storm-related impacts. Many communities in western Alaska have developed climate change vulnerability assessments, climate change adaptation plans, and hazard mitigation plans in response to coastal storms, erosion, and flooding. In addition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs authored a document describing the infrastructure needs of tribal communities and Alaska Native villages considering relocation to higher ground as a result of climate change. These documents can help communities anticipate, plan, and prepare for the impacts of climate change. Increasing community capacity for developing vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans can increase community preparation and implementation of actions to reduce local risks.

Data collection and forecasting tools

In order to assess Alaska’s coastal erosion and flooding hazards, major gaps in baseline coastal data must be filled. Despite progress over the last decade, the extensive Alaskan shoreline and a rapidly changing coastal environment require that datasets not only be collected for the first time in many places, but also updated or continually monitored. As an example of this data gap, the 453-mile coastline of Washington and Oregon has 27 tidal gauges that record sea level, sea temperature, and meteorological data. However, along Alaska’s 6,640 miles of coastline, there are 27 total tidal gauges (the majority of which are on the Gulf of Alaska coast), and no tidal gauges on the 1,500 miles of coastline between lower Bristol Bay and eastern Norton Sound. Installing additional tidal gauges would improve ocean observation data and help prepare communities for storms.

The main data used for the assessment of coastal flood and erosion hazards are orthoimages, topography, bathymetry, water levels, wave height and energy, continually operating reference systems, and sea-ice thickness and extent, all of which could be improved in Alaska. Local forecasts are also needed so that communities can prepare for storm-related impacts. Storm forecasts need to include wave runup (the uprush of water above the stillwater level caused by wave action on a beach or shore barrier) to accurately predict flooding.

Funding

Increasing funding for climate change response is the single most effective means to support communities in addressing the impacts of storms in coastal Alaska. One such funding example is the Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Signed into law in November 2021, the Act includes designated funds for village relocation and protection against flooding and erosion linked to climate change. In addition, the Denali Commission has a number of resources related to funding and federal programs for communities impacted by storms.

- Northwest Climate Change Adaptation Plans is a Hub resource that includes examples of climate change adaptation plans from Alaska.

- Northwest Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments is a Hub resource that includes examples of climate change vulnerability assessments throughout Alaska.

- Climate Adaptation Strategies for the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta Region is a report designed to help build the resilience of Delta resources and the people who depend on them. It includes specific examples of adaptation practices that could increase community resilience.

- Alaska’s Environmentally Threatened Communities is a StoryMap that tracks data and tools for 144 environmentally threatened Alaskan communities.

- The Denali Commission Village Infrastructure Protection Program and Denali Commission Grants and Funding pages provide information on funding for communities and individuals affected by disasters in Alaska.

- Alaska Coastal Mapping Gaps and Priorities is an assessment that identifies gaps in coastal mapping and priorities for improving data collection.

- Community-Based Methods for Monitoring Coastal Erosion is a guide that can help communities to measure and monitor the rate of coastal erosion.

- Shoreline Change at Alaska Coastal Communities includes maps of historical erosion and accretion rates for several riverine and coastal communities in Alaska.

- Alaska Water Level Watch is a collaborative group working to improve the quality, coverage, and accessibility to water-level observations in Alaska’s coastal zone.

- Alaska Climate Change Impact Mitigation Program provides technical assistance and funding to communities imminently threatened by climate-related natural hazards such as erosion, flooding, storm surge, and thawing permafrost.

- Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium’s Center for Climate and Health assists Alaska Native communities to better understand the impacts of climate change and how to adapt in healthy ways.

Information About Ex-typhoon Merbok

- Typhoon Merbok Pounded Alaska’s Vulnerable Communities at a Critical Time is an article written by Rick Thoman, climate specialist at University of Alaska Fairbanks, about the weather and climate implications and impacts of ex-typhoon Merbok.

- Ex-Typhoon Merbok Data Response StoryMap is an Alaskan Geospatial Office resource that includes community flood impacts, high water mark data, imagery, and more.

- An Interdisciplinary Approach to Coastal Resilience in Alaska is an Alaska Sea Grant webpage that discusses the impacts of ex-typhoon Merbok on Chevak, Alaska.