Reading Time: 6 minutes

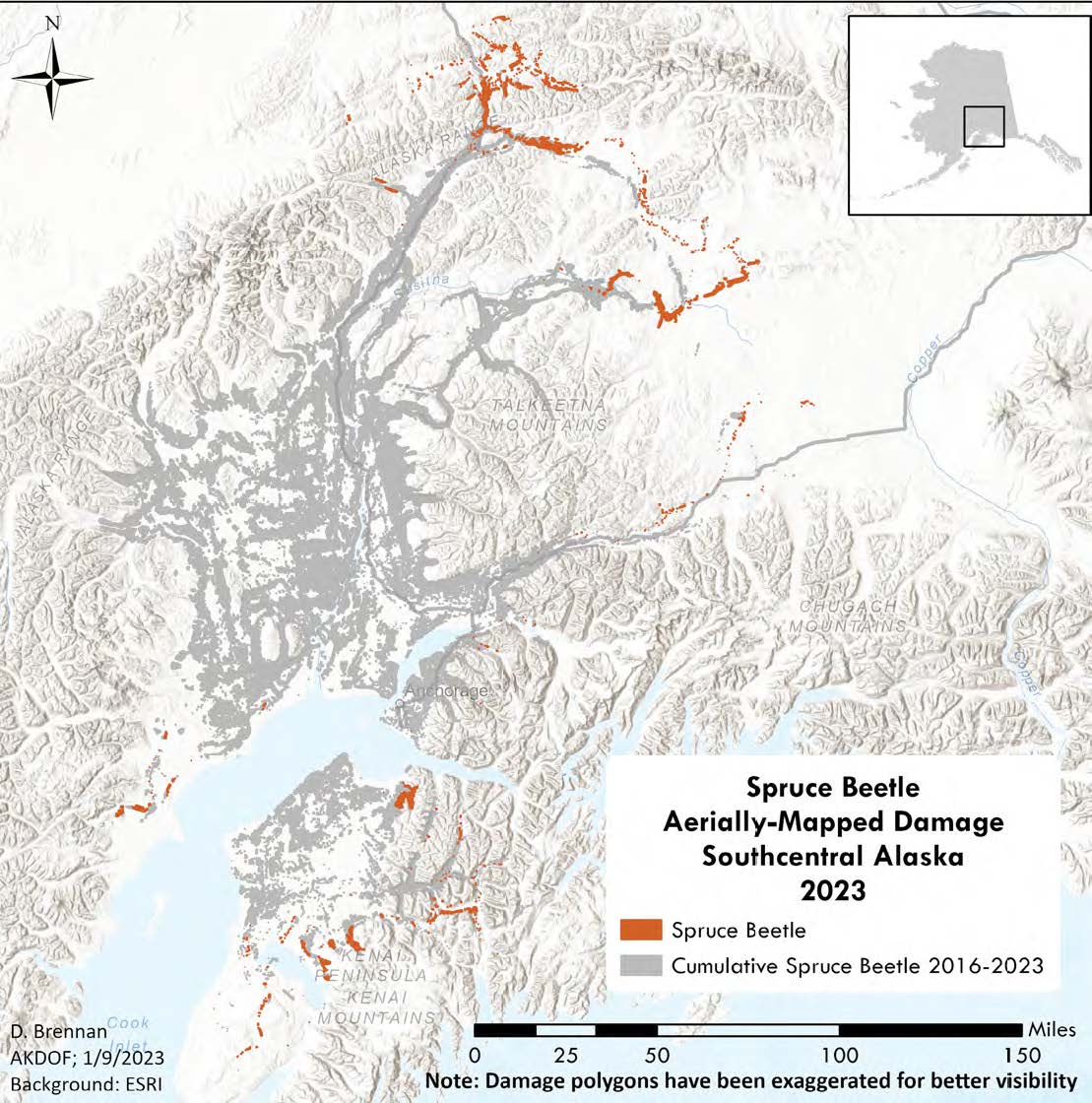

A spruce beetle (Dendroctonus rufipennis) outbreak has affected nearly 2.2 million acres of spruce forest in Alaska since 2016. From the Kenai Peninsula to just north of the Alaska Range in Healy, spruce beetles have infested and killed spruce trees, presenting a hazard to residents and recreationists, and changing forest composition. This outbreak coincides with increased temperatures and drought conditions associated with climate change. These conditions create a more favorable environment for spruce beetles, accelerating their life cycle and increasing the vulnerability of trees to infestation.

Spruce beetles are bark beetles that are native to Alaskan forests and beyond. They infest several species of spruce trees, including white spruce, Lutz spruce, and Sitka spruce. Black spruce can also be infested, though it is less common. The beetles burrow into the tree to lay eggs, targeting the phloem, a delicate layer of living tissue beneath the bark. The phloem carries nutrients produced in the needles down to the roots. When beetles damage the phloem, they cut off the tree's food supply, often leading to the tree’s death. Under normal population conditions, spruce beetles typically prefer recently downed or large, stressed, or dying trees. Because of this, spruce beetles play an important role in forest dynamics and decomposition. However, outbreak-level populations can infest standing, otherwise healthy trees, including smaller, younger trees.

Rising temperatures and drought contribute to spruce beetle outbreaks

Spruce beetle outbreaks are not uncommon in Alaska. However, climate change could affect the scale and location of outbreaks, intensifying impacts on spruce forests. Increased temperatures during the growing season allow some spruce beetles to complete their life cycle in one year instead of two, meaning more beetles can reproduce in a shorter time. Milder winter temperatures allow more beetles to survive the winter and complete their lifecycle. This reduces the natural decline of the beetle population. Rising temperatures and drought also weaken spruce trees. Drought conditions can make spruce trees more susceptible to spruce beetle infestation during outbreaks. Larger spruce beetle populations mean a greater likelihood of large-scale infestation in forests, even in younger, healthier trees.

Historically, spruce beetle outbreaks in Alaska have primarily affected the Southcentral region, particularly the Cook Inlet, Kenai Peninsula, and Copper River Basin, where extensive damage has occurred. Since 2016, a significant outbreak has affected over 2 million acres of forest in Southcentral Alaska and has spread northward into the Alaska Range. Although cold winter temperatures in Interior Alaska have controlled spruce beetle populations in the past, rising temperatures associated with climate change may make interior winters more hospitable for beetles, potentially leading to larger outbreaks in this region.

Prior to the most recent outbreak, the last large-scale outbreak in Alaska occurred in the 1990s and affected 2.5 million acres of spruce forest, 40% more forest area than was infested over the previous 70 years. During this outbreak, beetles killed more than 90% of trees larger than 11 cm. Other major outbreaks occurred in Southcentral and Southwest Alaska in the 1810s, 1870s, 1910s, and 1970s. As the climate continues to change, outbreak frequency could increase in many parts of the state.

Effects of spruce beetle outbreaks

The effects of a large-scale outbreak can extend beyond immediate harm to trees. For example, forest composition (the plants that make up a forest) can change after a large-scale outbreak. When large numbers of spruce trees die, gaps in the canopy create an opportunity for other plants, such as grasses and forbs (e.g., Canada bluejoint, fireweed), shrubs (e.g., willow, alder), and deciduous trees (e.g., birch, aspen). The types of plants that grow after a spruce beetle outbreak vary by the climate and soils of a specific location. Spruce trees will typically begin to grow again after several years. However, in the interim, altered forest composition can affect wildlife, water availability, and wildfire patterns.

Wildlife can be affected by changes to the plants that make up a forest and other factors associated with outbreaks. Some animal species may benefit from more insect activity (e.g., American three-toed woodpeckers), nesting site availability in dead standing trees (e.g., yellow-rumped warblers), or from the understory growth and forage created by the openings in the forest canopy (e.g., dark-eyed juncos, moose, Sitka black-tailed deer). However, species that rely on spruce trees for shelter or food, (e.g., red squirrels and Townsend’s warblers) can suffer during outbreaks. Negative effects on wildlife have been more pronounced in areas that were salvage logged than areas affected by outbreaks alone.

The accumulation of dead trees and limbs on the ground after an outbreak can affect fuels and fire hazard. In addition, after the 1990s outbreak, grass cover in the forest understory increased from less than 1% to nearly 50% in affected areas on the Kenai Peninsula. Fine fuels such as grasses and forbs can increase the likelihood of wildfire ignition and spread. Because wildfires can affect water quality and increase the risk of flooding and erosion, they can also affect salmon and other aquatic species.

Spruce beetle outbreaks can also have hydrological impacts. Though research on these impacts is limited in Alaska, in other parts of the country, such as Colorado, large spruce beetle outbreaks have significantly increased water yields, even up to 25 years post-outbreak. Similarly, a mountain pine beetle outbreak in Montana resulted in higher annual water flow, earlier peak flows, and increased low flow levels. These findings align with general observations that removing vegetation near streams, whether through fire, logging, or insect infestations, typically leads to increased and earlier peak flows and overall higher water yields. As trees begin to grow back, flows eventually return to normal.

Human health, safety, and sense of place can also be affected by outbreaks. Dead spruce that are standing or fallen can pose a threat to human safety, reduce access to recreational sites and wild foods, and impede access to routes used to escape wildfire or floods. An outbreak can also significantly alter the appearance of a forest, affecting resident and visitor sense of place and connection to the landscape. After 90% of spruce trees were lost to the 1990s outbreak, for example, “a keen sense of sadness” affected communities across the Kenai Peninsula.

In addition, in communities that rely on timber harvest, such as Ninilchik, a loss of timber resources associated with outbreaks can affect the economy for decades, particularly because spruce beetles typically target larger-diameter, older and more valuable trees. However, some communities have experienced short-term economic benefits from salvage logging after beetle outbreaks, and others have enjoyed more open vistas or opportunities to build more roads in a remote region with limited access.

Building resilience to future outbreaks

Climate change is likely to affect the frequency, size, and location of spruce beetle outbreaks in Alaska. The effects of recent outbreaks have extended far beyond the loss of trees, impacting wildlife, water resources, and human communities. Despite the challenges posed by recent outbreaks, there is hope that we can help Alaskan forests adapt. By understanding the factors driving spruce beetle outbreaks and the potential long-term effects, land managers and researchers can develop strategies to reduce impacts and build more resilient ecosystems. This may involve a combination of forest management practices, climate adaptation measures, and community engagement. To learn more about managing spruce beetle outbreaks in Alaska, visit the Alaska Spruce Beetle website supported by University of Alaska-Fairbanks, Alaska Department of Natural Resources, and the USDA Forest Service. For an example of how the Chugach National Forest is reducing spruce beetle damage on the Kenai Peninsula, visit this Adaptation in Action article.

A Guide to Tree Management Options for Home and Woodlot Owners is a webpage from University of Alaska-Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service that provides an identification guide and management actions for spruce beetle in Alaska.

Northern Climate Reports include projections and maps that display three broad levels of historical and projected climate-related protection from spruce beetle outbreaks in forested regions of Alaska.