Reading time: 3 minutes

Imagine a cool and clear salmon stream flowing from high-elevation forests through agricultural land, and eventually, out to sea. This stream is a vital ecosystem that can support plants and wildlife, the local economy, and cultural practices. But as the climate changes, the stream is likely to be affected by warmer water temperatures and reduced summer flows. These changes could impact salmon and other aquatic species, as well as surrounding forests and agricultural land. To maintain ecosystem health and address public needs, land managers must decide how to adapt to the effects of climate change.

For a farmer whose operation depends on stream water, adapting to these changes might include planting more drought-tolerant crop species, improving water management strategies to reduce water use, or planting a riparian buffer to reduce runoff. Foresters managing forest land in the area could accept higher levels of tree mortality associated with reduced water availability, or reduce stand density to reduce competition for water. Costs, impacts to other resources, timelines, and various other factors need to be considered in these decisions. These are just a few examples of the choices land managers can face when balancing multiple needs while adapting to climate change. Each decision has potential benefits and drawbacks, and finding the right solution often requires careful consideration of ecological, economic, and social factors.

To navigate the complexities of climate change and prioritize land management actions, managers can turn to climate adaptation frameworks. Developed by climate scientists and land managers, these frameworks provide a structured approach to decision making. By incorporating climate change into planning and projects, managers can identify the most pressing threats and prioritize actions that align with the most valued attributes of the land. This approach ensures that recommendations are objective, thoughtful, and informed by the specific needs of the landscape. In addition to helping land managers make informed decisions about climate adaptation, these frameworks can also help synthesize information that is needed for land management planning and project implementation.

What frameworks are available?

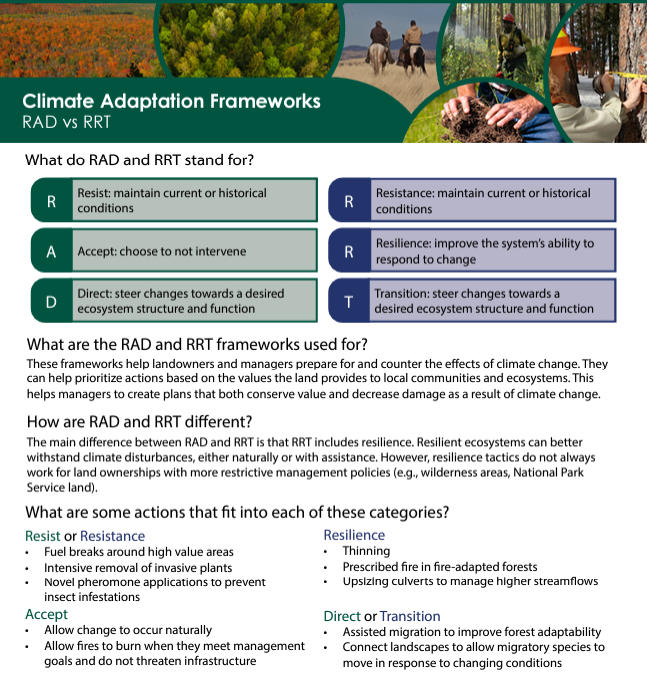

Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) and Resistance-Resilience-Transition (RRT) are the most commonly used climate adaptation frameworks. These frameworks were created by the National Park Service and the USDA Forest Service, respectively, and further work has clarified and refined these concepts (for examples, see this journal article and report).

These frameworks aim to help land managers move beyond managing for historical or pre-colonial conditions. They provide space to think about where a different management style might be appropriate, where it might not, and what to do in either situation. RAD and RRT are similar, but the main difference is that RRT includes resilience. Therefore, in places that require a more hands-off approach (such as National Parks or wilderness areas), RAD can be a better fit. In places where more active management is allowed (such as National Forests or private land), RRT provides more flexibility. It is also important to note that although RRT does not include “accept” as an option, the choice to do nothing is still a choice.

Terms defined

Resist or Resistance actions aim to maintain historical conditions. As time goes on, resisting change will likely become time-intensive and costly. Therefore, actions in this category are best for places or species that are irreplaceable and integral to ecological function or community livelihoods. They also work well in places that need to be managed for historical conditions. Examples of Resist or Resistance actions include:

- Novel pheromone application to protect a valued tree species from pest outbreaks.

- Aggressive removal of invasive plants to protect species that are valuable to local communities (e.g., sage-grouse, huckleberries).

- Fuel breaks to protect high-value areas with important species.

Resilience is one of the best tools managers can use to help species or ecosystems adapt to change. A resilient system can deal with fluctuations caused by climate change (e.g., drought or heavy precipitation) and maintain similar characteristics and functions. For example, resilience could help an agricultural area continue to produce the same type of crop, or a different variety of the same crop. The goal of actions that increase resilience is to retain ecological functions similar to (but not the same as) historical conditions. This is a great option for places that can allow for some degree of change and can also be actively managed. Examples of Resilience actions can include:

- Thinning or prescribed burning to decrease hazardous fuels, reduce competition between trees, and allow for trees to deal with other stressors associated with climate change (e.g., increased pests and disease).

- Planting trees in urban areas to reduce the impacts of urban heat.

- Improving soil health through practices like biochar application or cover cropping.

- Implementing farming practices (e.g. improving soil health with cover cropping or no-till) that allow for continued production in more extreme weather.

- Updating, upsizing, or removing infrastructure to ensure it is built for the future climate (e.g., larger culverts to deal with higher flows, public transportation that functions during extreme heat events).

Accept. In places that have already experienced significant climate change impacts, restoration or repair may be too costly or time intensive. It can also be beneficial to allow for natural change if local economies or habitats will not be harmed by those changes. Accepting change may be best when managers can or need to allow for natural changes. Accept actions can include:

- Allowing fires to burn in areas where they achieve resource management goals and do not present a threat to infrastructure.

- Allowing ecosystem transitions without intervening (e.g., a forest transitioning to a grassland).

Direct or Transition benefits places where change cannot be avoided, but active management can promote more beneficial pathways or options. This type of management directs a place into a new, desirable state that is different than it was historically, but also actively avoids other, less desirable states. This choice aims to maintain the value of a place. This can be done by assisting natural change or stewarding climate-informed changes. Direct or Transition actions can include:

- Assisted migration, the human-assisted movement of seeds from one area to another, can improve the climate resilience of forests. Within a tree species, genetic variation makes it easier for individual trees to adapt to different climates. As such, seeds and seedlings from warmer climates could be planted in areas that are currently cooler to match the warmer future climate of the area (e.g., Douglas-fir seeds from a lower-elevation, warmer, drier site could be planted at a higher-elevation, cooler, wetter site to match the future climate of that site).

- Connect landscapes to allow migratory species to move in response to changing conditions (e.g., connecting rivers and streams to areas that offer cold-water refugia may help fish adapt as water warms).

- Plant climate-adapted species that are resistant to spruce beetle infestation, such as birch or aspen, to replace stands of spruce trees decimated by spruce beetle outbreaks in Alaska.

How can the frameworks be used to make decisions?

Climate change adaptation frameworks share a common goal: to support the diverse needs of the land, nearby communities, and local flora and fauna. By understanding the unique values within a specific area, managers can make informed decisions that uphold and preserve these values, even as climate change interacts with other environmental stressors.

These frameworks also provide clarity and direction. When faced with an uncertain future, choosing a starting point can be a significant challenge. Adaptation frameworks help to narrow down the initial choices required to incorporate climate change into management decisions. From there, managers can assess potential changes, evaluate the impacts on the lands they manage, and develop an action plan tailored to address these changes.

As a relatively new approach, the implementation of these frameworks requires ongoing monitoring and adjustment. As decisions are made and implemented, managers can track outcomes and make revisions. This adaptive approach will ensure that the frameworks remain effective in addressing the evolving challenges posed by climate change.

-

Climate Adaptation Frameworks: RAD & RRT Factsheet

This article was developed from an article originally published on AgClimate.net with permission from the author.