Estimated Reading Time: 5 minutes

The vast rangelands of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington provide a wealth of resources and benefits to society, including livestock forage, wildlife habitat, healthy watersheds, and diverse natural resources. Northwest rangelands are home to a variety of vegetation types, including sagebrush steppe, intermountain grasslands, and pinyon-juniper woodlands. However, due to the size, diversity, and multiple uses of rangelands, ranchers and land managers face a variety of challenges in managing these landscapes for successful and sustainable livestock grazing. Successful managers will need to respond to these challenges.

Climate change is expected to further complicate rangeland management. Ranchers and land managers face rising temperatures and changing rain and snow patterns that are likely to increase the frequency of drought, wildfire, and extreme precipitation events in Northwest rangelands. These events could worsen livestock heat stress and soil erosion, degrade water quality and forage quality, and decrease forage quantity. Adaptive management that anticipates and responds to climate change dynamics can help maintain rangeland health and productivity, as well as livestock-based economies.

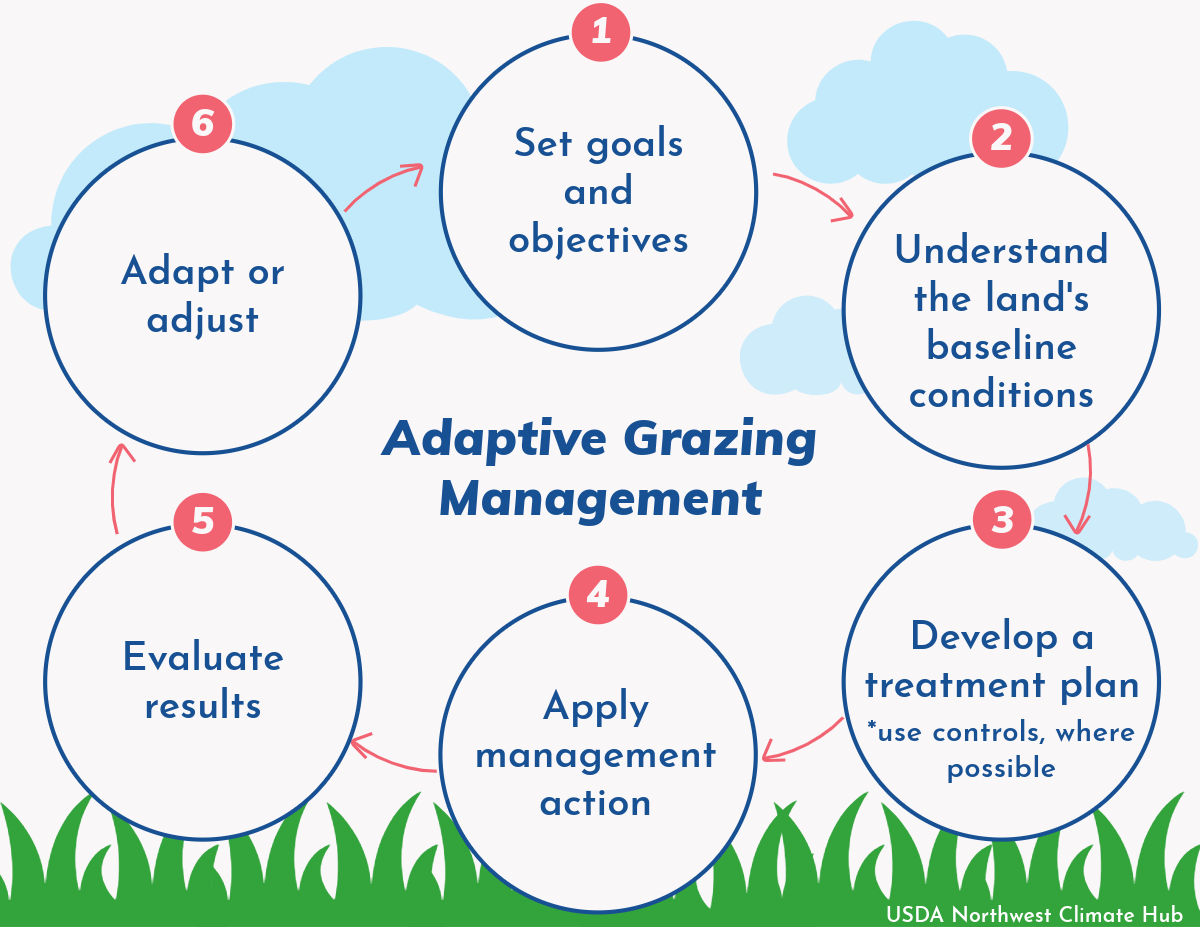

Adaptive Grazing Management (AGM) uses a feedback loop of learning to make decisions about grazing and other natural resource issues. AGM includes monitoring rangeland and livestock conditions to track how management actions affect indicators of success determined by the rancher or land manager (e.g., reduced invasive grasses, reduced soil erosion, improved wildlife habitat). Management actions can then be adjusted based on what these monitoring data show. This flexible approach treats grazing decisions as experiments, accounting for the uncertainty of managing complex and variable natural systems.

The Adaptive Grazing Management Process

Adaptive grazing management includes the six steps outlined below. These steps are iterative and are not always linear. For example, a manager may apply a management action, evaluate the monitoring data associated with that action, and notice that an action is having adverse effects. In response, a manager may return to step 3 to develop an improved treatment plan. Managers and ranchers using AGM will continue to go through these steps for as long as they choose to manage land adaptively.

1. Set specific goals and objectives

- Goals and objectives may include ecological, financial, social, or livestock production goals. Examples of goals include improving forage production for livestock, reducing invasive species such as cheatgrass, and reducing soil erosion. Setting goals with specific quantitative metrics can increase the likelihood of success.

2. Assess

- Assess rangeland dynamics. Before making land management decisions, gather information about the specific management area. Understanding the land's ecological baseline is crucial to monitoring changes over time and to interpreting change effectively. This includes assessing what kind of plants the land can support, the current health of plants, typical weather patterns, and the frequency, intensity, and variability of major climate drivers (e.g., drought) in that location. To do this, one might gather ranch records and photos, climate and ecological data from public websites (e.g., RAP), input from family, team members, technical experts, and peers, and collect field data to establish baselines conditions for ecological, social, financial, and livestock objectives.

- The Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health technical assessment from the USDA Forest Service, Agricultural Research Service, Natural Resources Conservation Service and partners, can help managers to assess rangeland conditions before establishing treatment and monitoring plans.

3. Develop treatment plans

- Identify strategies for action (treatment plan) and list how to track progress toward goals and objectives. Plans should be informed by science and associated with goals and objectives. Examples of ways to track progress include photo monitoring, grazing records, and pasture monitoring.

- Consider creating a conservation plan. These plans can further empower managers with tools like land-use maps, soil data, and economic analyses that can inform decision making. Organizations like the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) can help with conservation plan development.

- Consider constraints. Recognize and plan for potential roadblocks to achieving goals. These constraints can be diverse, including unpredictable weather, challenges in balancing different goals for the land, or not having enough workers to implement new practices. Good sources of information, such as weather forecasts, can help with planning ahead and preventing problems.

4. Apply management actions

- Implement management actions that are informed by monitoring data and based on goals and objectives. If possible, establish treatment controls or comparison treatments to better determine which actions make most progress towards goals.

- For example, if a new grazing strategy is attempted, consider applying the new approach on part of the allotment, and the baseline approach on a similar part of the allotment, to monitor and compare results.

- Research suggests that successful principles of grazing management include considering ways to improve stocking rates, using a grazing plan, prioritizing ecological health, evaluating distribution, prioritizing animal welfare, and engaging in activities that involve broader public interests and stakeholders.

- Some examples of management actions that might be used in AGM include adaptive genetic selection, rotational grazing, reseeding of native grasses, and flexible stocking rates.

5. Monitor and evaluate results

- Plan and implement monitoring plans and use the data to track the results of actions over time.

- Monitoring methods may track short- or long-term outcomes of your management plan. Monitoring methods should be simple, efficient, and consistent. Focus on areas where significant changes are likely or where information is unclear.

- Photo monitoring methods can track plan implementation and outcomes. See, for example: Idaho Cooperative Photo Monitoring webpage from the Bureau of Land Management and the Idaho State Department of Agriculture.

- For more information about vegetation monitoring methods, see this Monitoring Manual for Grassland, Shrubland, and Savannah Ecosystems and its second volume.

6. Adapt or adjust

- Examine the results of the management activities. Based on the monitoring data and local knowledge, determine whether goals have been met, and contemplate other possible adaptive actions. Consider discussing adaptive actions with land management agencies, technical advisors, and peers for additional feedback. Adjust actions to better meet goals.

- Set and adhere to pre-defined condition thresholds for action. These are sometimes called triggers, and may help managers respond to changing ecological, climatic, or social conditions. For example, managers may set a threshold for low spring precipitation that triggers use of drought strategies such as flexible stocking strategies (e.g., if precipitation accumulation on June 1 is 75% of the long-term average or less, reduce stocking rates by 25%).

AGM is a cyclical process that relies on continuous monitoring and adjustments. Ranchers and land managers adapt actions based on monitoring data, then continue to monitor for further changes, adapting to those changes as they arise. As such, the core principle of AGM is flexibility. By constantly monitoring and adapting their practices, ranchers and land managers can ensure their grazing strategies are sustainable and responsive to changing rangeland environments. In essence, AGM is a learning process. As ranchers gain experience and observe the land's response to their actions, they can refine their grazing practices for long-term success.

A Northwest example of Adaptive Grazing Management

In the Bear Valley near Seneca, Oregon, rancher Jack Southworth runs a cow-calf and yearling operation on 12,000 deeded acres and 30,000 acres of leased USDA Forest Service land adjacent to his ranch. Historical grazing practices, including early spring grazing and continuous grazing into June, had degraded much of the rangeland that Southworth depends on for his operation. To improve forage production, soil health, and resilience to climate change, Southworth adopted practices consistent with AGM. These practices are detailed below.

- Goal: Sustain a desirable plant community, high forage production, and healthy, well-covered soils to increase rangeland resilience to climate variability and change.

- Assess: Southworth learned when grasses on his land can sustain light to moderate grazing. He also identified typical weather patterns, and the frequency and intensity of climate drivers such as drought. He used perennial seed mixes that mimic some of the attributes of native grasses but improve forage production.

- Develop treatment and monitoring plan.

- Apply management actions:

- Reseed degraded, private rangeland pastures with perennial seed mixes.

- Delay grazing of native bunchgrass rangelands until later in spring when grasses have three-and-a-half leaves.

- Intensively graze relatively small areas at a time, then move cattle to new areas to allow plants a long time to recover before being grazed again. This can favor higher plant diversity and support higher yield.

- Monitor and evaluate results: How are grasses responding to this grazing management?

- Long-term monitoring tracks changes that occur in the plant community. Southworth measures: Plant species composition, plant density, and soil exposure. He monitors range conditions annually in the fall.

- Examine results: Diversified forage resources help Southworth maintain adaptability to climate drivers such as drought.

- Adapt:

- If bare soil increases over time, shorten a grazing period in spring to allow more plant growth before grazing. Alternatively, postpone grazing until plants are dormant and more brittle. This allows for greater accumulation of dead stems and leaves on the soil.

- Adapt seed mixes to reduce the need to reseed.

Through iterative implementation of these steps, Southworth has witnessed enhanced profitability, better soil cover and protection, healthy wildlife populations, robust willow growth in riparian zones across both the ranch and leased lands, and greater capacity to dedicate time and resources to community involvement. To learn more about Southworth’s rangeland management work in the Bear Valley, check out this Washington State University Extension case study and video.

Collaborative considerations

Rangeland-based livestock operations in the Northwest often depend on access to public rangelands for forage throughout the year. On these lands, decisions about AGM processes can bring land managers, ranchers, and other interests together to identify and implement new adaptive strategies that address climate and weather variability and livelihood goals at the same time. The Southworth case study and video discuss the importance of these kinds of collaborations. For another example from a different region, see this study from the Prairie Pothole region.

Key word: adaptive

AGM is not a one-size-fits-all solution. It is a flexible approach that helps managers deal with the uncertainties and complexities of Northwest rangelands. Effective implementation of this approach includes considering local factors like weather patterns and the specific limitations of each ranch or grazing area. By following a structured process, managers can set clear goals, experiment with new ideas, and learn from both their successes and failures. This ongoing cycle of learning and improvement allows them to make better decisions for their land over time. As such, AGM helps ranchers and rangeland managers adapt to the challenges of climate change in real time.

“Adaptive Grazing Management in Semiarid Rangelands: An outcome-driven focus” is a journal article that explores the specifics of AGM.

Applying Adaptive Grazing Management – this factsheet from the University of Idaho walks producers through the process of applying AGM on rangelands in Idaho.

The Landscape Toolbox – Tools and Methods for Effective Land Health Monitoring – this USDA Agricultural Research Service site includes information and resources for interpreting and monitoring rangeland health.

Climate Change Vulnerabilities and Adaptation Strategies for Land Managers on Northwest US Rangelands is a research paper written by USDA Northwest Climate Hub scientists and partners that provides a synthesis of key vulnerabilities to climate change for Northwest US rangelands.

*The steps in this Adaptive Grazing Management plan are complimentary to the USDA NRCS Conservation Planning Process. This page has been informed by that process.